I have just made a momentous decision. I shall go over to the counter-attack, that is to say here, out of the Ardennes, with the objective Antwerp!

I have just made a momentous decision. I shall go over to the counter-attack, that is to say here, out of the Ardennes, with the objective Antwerp!

With a sweep of his hand, Hitler had just laid the foundation for the German counter-offensive that would become more known as the Battle of the Bulge. The German generals and field marshals surrounding the large situation map in the Fuehrer Headquarters war-room were momentarily stunned and with good reason. Assembled at Hitler’s military headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, they had only moments before heard the all too familiar litany of reverses and losses briefed by Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, Chief of Staff, Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW). The fortunes of war were not looking favorable for Germany on Sept 16, 1944. Strategically, the Germans were on the run.

The Allied advance across western Europe following the breakout in Normandy had carried right to the vaunted Siegfried Line defenses of Germany’s border. American units had already penetrated onto German soil near Aachen.

On the Russian Front, the Soviet summer offensive had crossed into East Prussia. Allied bombing was crippling German industry and devastating her cities. The once-mighty Axis alliance was falling apart, as one by one Germany’s allies, save an isolated Japan, defected, surrendered, or were overrun. German losses in men and material were tremendous, and worse, non-recoverable. Combined German military losses during June, July, and August 1944 totaled at least 120.000 dead, wounded, and missing. Everywhere the German military was on the defensive. It was a period of crisis, and desperation, for Germany.

With this backdrop in mind, Hitler would try one last gamble, a surprise attack upon the unsuspecting Allies on the Western Front. Hitler was betting that a successful operational-level offensive in the west would have strategic results. The stakes were staving off defeat just long enough for the German secret weapons to turn the tide of the war or the destruction of the last remnants of German combat power and the hastening of her defeat.

The operational situation of the Allies in the west actually presented the conditions that would favor a large-scale enemy counter-offensive. Although advancing ceaselessly throughout August and into September, the Allied armies were on the verge of outrunning their supply lines. The Broad Front strategy of the Allies already had the advancing army groups competing for supplies. Strains within the alliance, though personality-driven, were emerging. The German West Wall Defenses, the infamous Siegfried Line, would serve to fix and hold the Allies as they gathered their strength over the winter months.

By November 1944, the Allies had reached their operational culminating point. The beginning of December, the originally planned – time for the German offensive, saw the Allied armies settled into a static front, positioned along or astride the West Wall. Although limited offensive operations were continuing, by and large, the Allies were gathering their strength for a full-scale resumption of their offensive in the coming months. They expected the Germans to attempt a defense of the West Wall coupled with the usual local counter-attacks. They did not anticipate a full-scale counter-offensive, especially in the Ardennes area. The German operational situation, though bleak, offered the glimmer of a brief respite by November 1944. German Army units had been in full retreat across the occupied countries since late July. However, now they were on German soil and fighting for German survival. Throughout the battered ranks, this was well understood, as the German fighting spirit began to stiffen. Furthermore, the recent German success in Holland, where they defeated the Market Garden attacks, and the American repulse in the entire area of the bloody Hürgten Forest fighting, reduced the sense of shock from the great German rout of August.

The Hürtgen Forest Trenchs most importantly, the German Army had fallen back on its lines of communication and had occupied excellent defensive terrain along the German border. Additionally, there was the West Wall. Although the much-vaunted Siegfried Line was a mere shell of its former self by November 1944, it did present a formidable obstacle to the advancing Allies. As the German Army units settled into their aging bunkers, just a step ahead of the Allies, their High Command steeled themselves for a defense of the West Wall. They would defend for as long as possible, attempt to rebuild their depleted strength and delay what was now considered the inevitable defeat.

Coupled with the Allied overextension and pause at the border, the German defensive activity brought quiet along the line of opposing Armies. By December, the area of the Ardennes could be called a Ghost Front, as both sides settled in for a long cold winter. Both, German and American Armies alike, viewed the Ardennes as a quiet nonvital sector, where troops could be rotated in for a stretch of rest in the Wehrmacht’s case, or for seasoning of green units like the 106th Infantry Division or the 99th Infantry Division in the case of the Americans.

The prevailing weather and terrain of the Ardennes both aided this mutual impasse. The winter Ardennes weather could be expected to be unfavorable for large-scale operations. Extremely cold weather and wet conditions would make life miserable for soldiers. Snow, sleet, or freezing rain grain would be anticipated almost every other day. Overcast skies were normal, and the fog was not uncommon. If the ground was not frozen solid and covered with snow, then it was a quagmire of mud. The winter of 1944, particularly, would be one of the coldest Europe was to see for years, and secret German weather stations forecast a period of cold, fog, and low clouds for December.

The terrain was equally challenging. The Ardennes is an area of dense, coniferous forests traversed by several ranges of low mountains and hills. Although hills and trees predominate, the terrain is interspersed with the fields of local farmers. Several watercourses crisscross the region. Most are characterized by steep gorges and banks, and deep swift waters. An extremely limited and restrictive road network serves to link the numerous towns and villages that dot the area. In essence, the Ardennes is a rugged campaigning country. The prevailing weather and terrain would serve to negate the tremendous American advantages of overwhelming air power and masses of material.

Conditions in the Ardennes, at once, would offer the Germans the conditions for a stubborn defense, and the possibility of a surprise attack. They had done it before. The German Army had swept through the Ardennes unexpectedly in May 1940 during the invasion of Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, and France. Perhaps it was this that put the idea in the Führer’s head, but Hitler saw the inevitable defeat of Germany, given its current situation. His strategic concept: a bold, unexpected offensive that would split the advancing American and British Army Groups on the ground, and also split what he saw as a strained Anglo-American political alliance.

The goal was to delay the Allied advance and enable Germany to apply the power of her Wonder Weapons against the enemy. It was reasoned that this might result in a negotiated peace in the west, allowing Germany to turn her full might eastward for the ensuing defeat of Russia. The sleepy Ardennes Front offered the ideal spot. The American sector was very lightly held as green units were stretched thin defending over-extended frontages. The Allies would never expect a major attack in the Ardennes as the sector was not considered favorable for a large-scale offensive. Besides, most intelligence reports indicated that the German Army was beaten, and not capable of an attack.

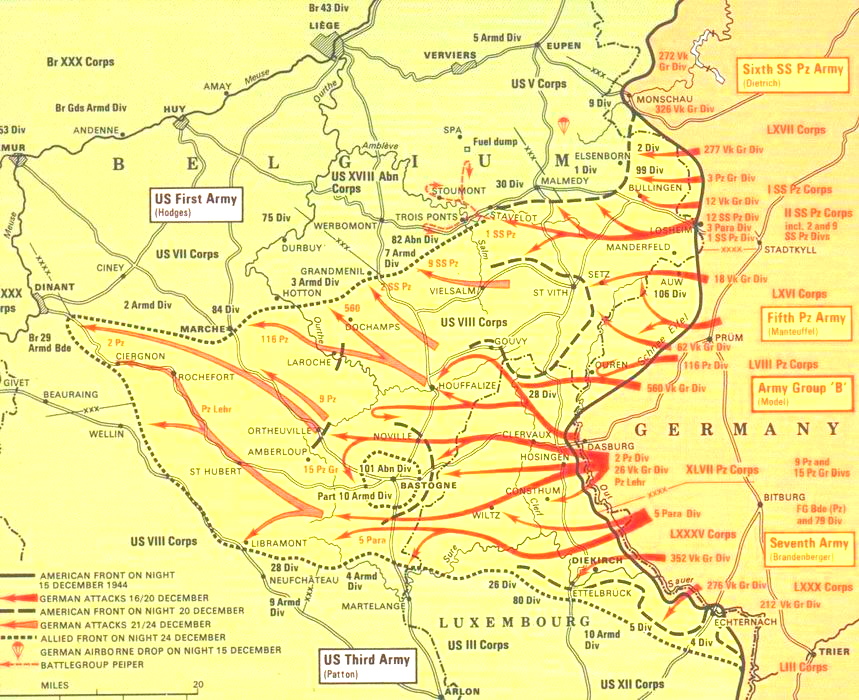

The plan conceived by Hitler and his staff was deceptively simple. Under the cover of darkness and poor weather, the Germans would launch a massive surprise attack at the weakest point in the Allied lines, the center of the Ardennes. The main effort would penetrate the center of the line and reach for operational objectives while supporting attacks were made on the flanks to hold the shoulders of the breakthrough, fix allied forces, and protect the flanks.

Within the main effort, attacking infantry divisions would first create the penetration of American lines. Then, operational-level, forward detachments, would race forward through the gaps to secure deep objectives to ensure the unhindered advance of the main attack. These critical objectives took the form of the Meuse River bridges. The main body, the Panzer formations, would pass through these detachments and then continue the attack to the decisive objective – Antwerp.

One key problem existed; the Meuse bridges were almost 75 miles behind American lines. Surely, the Americans would react and deny the use of the bridges through destruction or defense before the forward detachments might get to them, or counter-attack the exposed flanks of the penetration. The solution was unconventional and equally as bold as the offensive itself a pair of operations to snatch the bridges right from under the American’s noses and block American reinforcements. German special operation forces would operate ahead of the army’s forward detachments to seize the critical crossings intact before the stunned defenders could react. They would hold the bridges long enough to hand them over to the forward detachments.

Fallschirmjaeger Troops (Airborne) would parachute in at night behind the lines to seize key crossroads to block the expected American counter-attacks. The entire plan was constructed on a delicate timeline. Speed was all-important to the success of each part of the operation. The offensive had to reach its initial objectives before the Allies could react. Likewise, achieving initial surprise was equally critical. Although many senior German leaders had their doubts about the entire operation, this offensive could presumably change the course of the war.

Fallschirmjaeger Troops (Airborne) would parachute in at night behind the lines to seize key crossroads to block the expected American counter-attacks. The entire plan was constructed on a delicate timeline. Speed was all-important to the success of each part of the operation. The offensive had to reach its initial objectives before the Allies could react. Likewise, achieving initial surprise was equally critical. Although many senior German leaders had their doubts about the entire operation, this offensive could presumably change the course of the war.

The idea of employing special operations to support the main operation also sprang from Adolf Hitler.Several issues motivated Hitler to consider the special operations that were to support the offensive. Most important was that of operational necessity. The Meuse River was the most formidable water obstacle between the offensive’s points of departure and the decisive operational objective. A major and unfordable watercourse, which posed a natural line of defense that a withdrawing army could rally upon and renew its strength, and use to delay an advancing opponent.

The idea of employing special operations to support the main operation also sprang from Adolf Hitler.Several issues motivated Hitler to consider the special operations that were to support the offensive. Most important was that of operational necessity. The Meuse River was the most formidable water obstacle between the offensive’s points of departure and the decisive operational objective. A major and unfordable watercourse, which posed a natural line of defense that a withdrawing army could rally upon and renew its strength, and use to delay an advancing opponent.

In the spring of 1940, the assault crossing of this river was a major event for the Germans in their first offensive through this area. It would take time to cross this river, which was over 75 miles behind the front lines. Despite the most rapid German advance, the Americans would have adequate time to defend, and very likely, destroy the bridges over the Meuse before the armored spearheads could hope to reach them. The tempo of the offensive was fast-paced, and the operational objectives would have to be seized within a week so that the Allies could not effectively react.

It was vital to capture the Meuse crossings intact to maintain the momentum of the attack. A delay at the river could spell disaster for the offensive. Additionally, the strong American forces pushing eastward the Aachen sector posed the threat of an immediate counter-attack from the north. Delaying this counter-attack would allow the spearheads to reach the Meuse unimpeded. Another reason for considering the employment of special operations was the precedents established by the Germans earlier in the war. Special operations forces had been used several times to conduct deep operations in pursuit of operational campaign objectives. The seizure of the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael is an excellent example of this technique.

In May 1940, a glider-borne commando detachment swooped down on the impregnable fortress in a surprise air assault operation ahead of the main German forces. The commandos, members of an elite special military unit, the Brandenburgers, paved the way for the conventional spearhead to continue its attack unimpeded. The small force of 86 men had accomplished a task that had a significant operational-level impact.

Likewise, Hitler and the German military witnessed the Allies employ just this sort of tactic successfully against them in almost every campaign of the war. The month previous to the formulation of the offensive plans, September 1944, saw the concept carried to the extreme as the Allies attempted to size the multiple bridges that lay in the path of the British XXX Corps’ advance during the airborne phase of Operation Market-Garden. Additionally, up through October of 1944, elements of the German military had displayed a certain flair for conducting unorthodox, unilateral, strategic-level special operations as well.

Of the most notable German Special Operations, it is of no small coincidence that a certain Otto Skorzeny was involved in them. The success and dramatic rescue of Benito Mussolini from atop the Gran Sasso in Italy, the daring, but costly, airborne raid to capture Marshall Tito in Bosnia, and the abduction of Admiral Horthy’s son to keep Hungary in the war on Germany’s side, all serve to illustrate Germany’s ability to conduct unique special operations when the situation warranted such an approach.

Of the most notable German Special Operations, it is of no small coincidence that a certain Otto Skorzeny was involved in them. The success and dramatic rescue of Benito Mussolini from atop the Gran Sasso in Italy, the daring, but costly, airborne raid to capture Marshall Tito in Bosnia, and the abduction of Admiral Horthy’s son to keep Hungary in the war on Germany’s side, all serve to illustrate Germany’s ability to conduct unique special operations when the situation warranted such an approach.

Countless other smaller and less significant special operations were conducted by the Germans against both the Allies and the Soviets. Bold and daring, often conducted against the odds, the reports of these operations never failed to thrill Hitler and capture his imagination. So did the apparent American use of special operations teams in the recent successful operations to seize Aachen, Germany, just that October of 1944. German intelligence had reported to Hitler that operatives of the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) had conducted operations during the advance to that city clothed and posing as German soldiers. This and similar operations of the American OSS and the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) did not go unnoticed by German intelligence services or Hitler. Hitler, always enamored with secret weapons and daring operations, and at ways willing to go ‘tit-for-tat’ with the enemy, grasped the potential utility that such covert forces offered. A force operating behind enemy lines in the guise of the enemy presented numerous opportunities to have an impact on the defenders out of all proportion to their size.

This coupled with more orthodox paratroopers operations might also be a useful economy of force measure against the numerically and materially superior Allies. Although the ultimate success or failure of the offensive would not hinge upon the special operations, they would offer the potential for greatly increasing its probability of success. Finally, one last reason for attempting the special operations existed. For Germany, this was a time of desperation. Wacht am Rhein was a military gamble with very high stakes. The survival of Germany was at risk, and every resource that could be marshaled and thrown at the Allies was required to ensure a winning hand. It was hoped by Hitler that the unfolding German special operations would be one of the needed wild-cards.