Document Source & Purpose: This archive examines Claire Lee Chennault as a military theorist and campaign planner. It inquires whether Chennault’s evolution of a theory of war assisted his planning of the China-Burma-India Campaign during World War II. The document is divided into four sections. The first section focuses on the historical background of Chennault and the war in Southeast Asia, emphasizing the war in China as this is where Chennault preponderantly fought. In addition, it identifies the aims of the major belligerents of the Sino-Japanese War and why the Chinese actions were important to the Allied cause. The second section explores Chennault’s theory of war. This section explores how he developed his theory of war and the theory itself. The third section analyzes how Chennault’s theory met the Chinese and American ends (desired end-state), means (application of the available resources), and ways (resource employment to achieve the ends). The fourth section concludes that Chennault’s theory of war assisted him in planning the China-Burma-India campaign during the Second World War. By Maj John M. Kelley

(Definitive Version by Doc Snafu on October 26, 2022)

Two functions precipitated from Chennault’s theory of war. First, his theory clarified the past and the present; notably the Great War and airpower’s technological evolution. Second, it assisted Chennault to foresee the future. The future was realized because Chennault transcended the theorist’s role to that of an operational commander. His theory fostered an operational concept, the war of mobility, which developed into a fighting doctrine. With these resources and the invaluable contributions of the Chinese peasants, Chennault devised a method of employment that maximized the contributions from all means. Chennault rationally created a campaign plan designed according to his theory.

At every crossing on the road that leads to the future,

each progressive spirit is opposed by a thousand men appointed to guard the past.

Maurice Maeterlinck

INTRODUCTION

Between 1937 and 1945, the world’s attention was riveted to the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific. Yet, there was a theater of war in China and Southeast Asia that was a fight for survival for the Chinese and Japanese. While other nations such as Italy, Germany, France, and the Soviet Union eventually departed the theater for other battlefields, the US and the British stayed the course for the duration of the war. Yet, the US and the UK scarcely agreed on a common goal while campaigning in the theater. Whatever the sensibility of the divergent execution of the US and the UK southeast Asian strategy, the China Burma India Theater contributed to the ultimate defeat of Japan. The allied successes in China Burma India were all out of proportion to their meager costs. The addition of the allies to the theater prevented Japanese expansion into the Indian Ocean and, more importantly, kept China in the war.

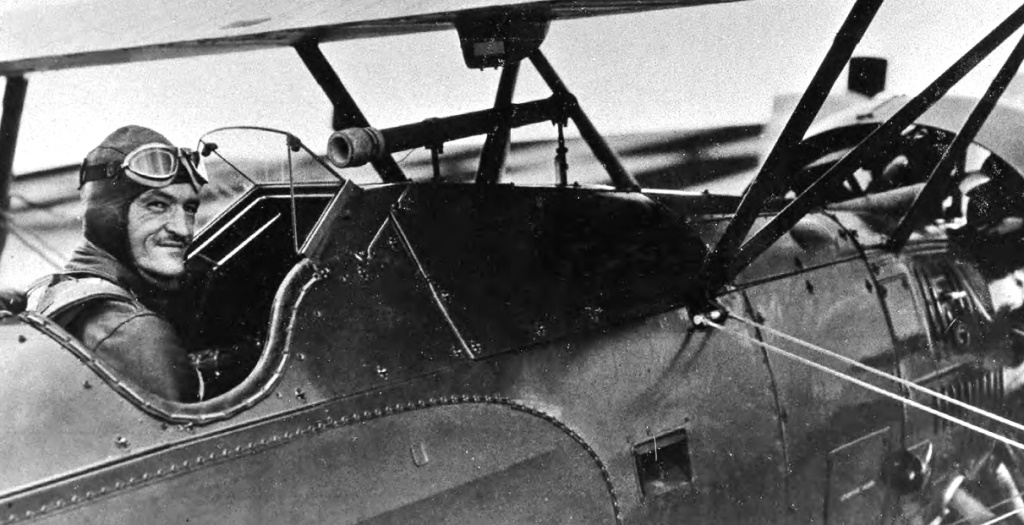

A large portion of the credit for the allied success in frustrating Japan’s designs in the CBI Theater rest with Claire Lee Chennault, the Flying Tiger. Chennault is renowned as a practitioner of aerial warfare in China. He did not command the theater, the Chinese, the Russians, the British and the Americans had their own command structures. Yet, he was largely responsible for the campaign through his advice to Chiang Kai-shek, and the precedent established for the allies when the US and UK entered the theater at half-time. His Fourteenth Air Force, really no larger than a composite wing, had an impact against the Japanese disproportionate to its modest size. His 308th Bombardment Group had the highest accuracy of any B-24 group. His 23rd Fighter Group had the greatest number of aerial victories of any US fighter group. His early warning net saved countless American and Chinese lives by giving them time to reach air raid shelters. His fliers held the record for the number of repatriations after a shoot-down or ditching. Chennault’s intelligence net (precursor to the OSS Asian Operations) continued to aid the Nationalist Chinese against Mao’s communists. One of Chennault’s Civil Air Transport planes was the last aircraft to deliver relief supplies to the besieged French garrison at Dien Bien Phu. The CIA eventually purchased his fleet and incorporated the clandestine air service into its operations.

A large portion of the credit for the allied success in frustrating Japan’s designs in the CBI Theater rest with Claire Lee Chennault, the Flying Tiger. Chennault is renowned as a practitioner of aerial warfare in China. He did not command the theater, the Chinese, the Russians, the British and the Americans had their own command structures. Yet, he was largely responsible for the campaign through his advice to Chiang Kai-shek, and the precedent established for the allies when the US and UK entered the theater at half-time. His Fourteenth Air Force, really no larger than a composite wing, had an impact against the Japanese disproportionate to its modest size. His 308th Bombardment Group had the highest accuracy of any B-24 group. His 23rd Fighter Group had the greatest number of aerial victories of any US fighter group. His early warning net saved countless American and Chinese lives by giving them time to reach air raid shelters. His fliers held the record for the number of repatriations after a shoot-down or ditching. Chennault’s intelligence net (precursor to the OSS Asian Operations) continued to aid the Nationalist Chinese against Mao’s communists. One of Chennault’s Civil Air Transport planes was the last aircraft to deliver relief supplies to the besieged French garrison at Dien Bien Phu. The CIA eventually purchased his fleet and incorporated the clandestine air service into its operations.

Back in the dark days of December 1941, his Flying Tigers were one slender thread of Allied hope. Chennault’s public legacy is that of the Flying Tiger, but there was much more to the man. From 1937 until recalled to the Army in April of 1942, Chennault was Chief of Staff of the Chinese Air Force and subordinate to Chiang Kai-shek. From his observations of the German, Italian, British, Russian, Chinese, and Japanese methods, Chennault deduced their fighting strengths and weaknesses. He was responsible for assisting Chiang in achieving Chinese strategic goals and, after recall and promotion to Brig Gen, he was responsible for assisting the US in achieving its strategic aims.

Back in the dark days of December 1941, his Flying Tigers were one slender thread of Allied hope. Chennault’s public legacy is that of the Flying Tiger, but there was much more to the man. From 1937 until recalled to the Army in April of 1942, Chennault was Chief of Staff of the Chinese Air Force and subordinate to Chiang Kai-shek. From his observations of the German, Italian, British, Russian, Chinese, and Japanese methods, Chennault deduced their fighting strengths and weaknesses. He was responsible for assisting Chiang in achieving Chinese strategic goals and, after recall and promotion to Brig Gen, he was responsible for assisting the US in achieving its strategic aims.

While he remained true to his President and country, Chennault’s wisdom, foresight, and insatiable desire for achievement eventually collided with the Army leadership. This conflict drove him to his third retirement from the Army and he departed China on August 8, 1945. By this date, Chennault had long proven and vindicated all his theories of war. While his mastery of aerial warfare is a legend, Chennault’s scholarly excellence is lesser-known. As a boy, he became well-versed in ancient history and the American Civil War. He received a formal education of the times, but his best education was first self-taught from the experience of self-reliance, and later, from diligent study of his beloved profession. As a lieutenant in Eddie Rickenbacher’s old Hat in the Ring Squadron, he quietly learned dogfighting in 1920 from World War I aces Maj Carl Spaatz and Maj Frank Hunter (later, CoS USAAF and CO of the Eighth Fighter Command, respectively).

Chennault quickly realized that the dogfighting tactics of the Great War were relics of the past. He called it a superb sport, but not war. Dogfighting had too much of an air of medieval jousting … and not enough of the calculated massing of overwhelming force so necessary in the cold, cruel business of war. Dogfighting dispersed force and firepower. In 1933, he predicted that the next war would open with a vigorous, concentrated air offensive. Chennault was rapidly formulating a mental compendium of tactics, doctrine, and operations to exploit this new weapon.

Chennault’s numerous articles, his school text, his testimony dating from his instructing at the Air Tactical School (ATS), and his memoirs, Way of a Fighter, reveal a great military theorist. Since the publication of his first articles while department head of the Pursuit Section in the ATS and his criticism of the Douhet Bomber advocates, his critics were out to destroy him. Several writers tried to disavow both Chennault and his war record. He was accused of disloyalty to the country, insubordination, black marketing, profiteering, sexual impropriety, lying, sloppy staff work, undisciplined units, and even fighting under an assumed name. Leaving the myths and his detractors behind, we shall concentrate on the man’s words and actions. It clearly becomes evident that Chennault was a genius in aerial warfare and a superb military theorist, doctrinaire, and a joint and combined operational artist.

This archive analyzes Chennault as a theorist and campaign planner. It will explore the development of Chennault’s theory of war. The paper will resolve the question: Did Chennault’s development of a theory of war assist him in planning the China Burma India Campaign during WW-2? The document has four sections. The background section establishes the historical framework for Chennault’s professional development, his understanding of war, and the China Burma India Theater. The war in China is emphasized in this section as this is where Chennault primarily fought. The theory section establishes the relevant Army theory of war at the US entry into the war. The evidence for this section relies heavily on Chennault’s pre-war writings and testimony. These writings introduce Chennault’s theory of war and its evolution. The third section describes and then analyzes Chennault’s desired end state (defeat of Japan), his means (his requested, projected, and use of actual theater resources), and his ways (application of his resources toward achieving his desired end state). The final section answers the research question and offers implications for military theorists, operational artists, and doctrinaires.

In the time of war the rebel against accepted doctrine who wins is decorated, promoted, and hailed as a great military captain, but in times of peace, the nonconformist is looked upon as a troublemaker. He is seldom marked for promotion to a higher rank and is generally retired or induced to resign.

Gen George C. Kenney

BACKGROUND

Like the Phoenix, Chennault rose from the ashes of rejection, and his second forced retirement to become Old Leatherface of the Flying Tigers, but his accomplishments were not only based upon his flying skills. Chennault fostered the myth that he was unprepared for the war in China. Madame Chiang asked him to organize a combat mission when he had been in China for less than two months. Chennault wrote that he started planning for the war with only the vaguest knowledge of the two opposing forces. The facts are different. No one was better prepared to fight the Japanese from such an austere theater, to project intellectual capital into aerial warfare, and to see the mission through with a titanium constitution regardless of the setbacks. Chennault was a consummate, open-minded, professional educator with the right balance between theory and practice. He was in his element when he worked independently. Alone, he would quickly estimate a situation and take action. He became defensive when asked to explain his thoughts or actions. It is this trait that eventually caused him difficulty with superiors.

At six years of age, he spent nights alone in Louisiana‘s wild Tensas River country gaining self-confidence and the ability to make his own decisions. Chennault recalls that he pored over history books in my grandfather Lee’s library reading about Peloponnesian and Punic wars. He also read his father’s books on Plutarch, Hannibal, Sam Houston, Stonewall Jackson, and Robert E. Lee. His early and sustained interest in history, geography, and mathematics allowed him to complete three grades in one year. Even his first interest in the Bible was not based upon faith but an interest in Biblical history.

At six years of age, he spent nights alone in Louisiana‘s wild Tensas River country gaining self-confidence and the ability to make his own decisions. Chennault recalls that he pored over history books in my grandfather Lee’s library reading about Peloponnesian and Punic wars. He also read his father’s books on Plutarch, Hannibal, Sam Houston, Stonewall Jackson, and Robert E. Lee. His early and sustained interest in history, geography, and mathematics allowed him to complete three grades in one year. Even his first interest in the Bible was not based upon faith but an interest in Biblical history.

His earliest military training occurred as a cadet at the Louisiana State University, although he graduated from Louisiana State Normal School to qualify for the teaching profession. He mastered several teaching jobs.

His earliest military training occurred as a cadet at the Louisiana State University, although he graduated from Louisiana State Normal School to qualify for the teaching profession. He mastered several teaching jobs.

In April 1917, he enlisted, and soon was a ninety-day wonder Infantry Lieutenant dourly drilling aviation cadets. After four rejections, Chennault was accepted into flight school and earned his coveted pursuit of pilot wings. His unit was en route to France when the Great War ended. Eventually, Chennault was assigned to the Hat in the Ring Squadron at Brooks Field, Texas. Here he quickly experimented with his new tactics. Chennault later reflected that the happiest days of his Army career were from 1923 to 1926 while stationed at Luke Field, Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Chennault’s familiarity with the Pacific Theater and the Japanese threat matured during his three years as commander of the 19th Pursuit Squadron at Luke Field. There, Chennault’s embryonic concepts of an early warning net, fighter squadron doctrine and tactics, the geopolitics of the Pacific Basin, and his criticism of the Army Air Corps canned exercises developed. In hindsight, it is odd that the US military’s use of an early warning net should arise from a lieutenant’s placing two observers with binoculars atop the Pearl Harbor water tower during exercises and alerts in the mid-1920s.

Japan’s reaction to America’s passage of the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 motivated Chennault to put his squadron, without higher directives, on alert and conduct armed patrols for six weeks – sixteen years too early. Chennault carefully trained his squadron in the mass attacks he had visualized in 1919. During wargames, the 19th Squadron’s attacks were so successful that the Navy sent representatives to copy the tactics while the Army commended Chennault for authoring a tactical manual. Sadly, the air arms did not adopt the tactics until well into WW-2. This solid tactical foundation, which matured over time as an instructor back at Brooks Field, added to Chennault’s intellectual capital. Col John F Curry recognized Chennault as the Air Corps’ best pilot and chose him to lead the Army’s precision flying team, the ‘Three Men on a Flying Trapeze’. Curry saw the team as an Army promotion. Chennault used the team as an opportunity to practice and promote the fighter theory he developed independently. Chennault later learned that many of his tactics were pioneered earlier by Oswald von Boelcke, the German WW-1 ace, and the father of fighter tactics. Chennault summarized the tactics using the military truism that the difference between the firepower of two opposing forces – all other factors being equal – is not the difference in the number of fire units, but the square of the difference in the number of fire units.

This meant that two fighters attacking one enemy had odds not of 2 to 1, but of 4 to 1. Chennault perfected the tactics of aerial mass and teamwork by connecting his three planes together with ten-foot strands of rope. Chennault, William MacDonald, and John Williamson then amazed crowds by flying their attached planes as one through violent maneuvers without cutting the ropes. In addition to teamwork and formation tactics against bombers, Chennault was analyzing how to solve the extremely time-sensitive intelligence problem of bomber detection and interception.

Over the next seven years, Chennault refined his theory and doctrine while a student, instructor, and department head at the ATS. In addition to these duties and leading the Flying Trapeze, he immersed himself in the study of warfare. At the ATS, faculty, and students debated theories of war, air power’s merit, the Billy Mitchell affair, and the theories of Giulio Douhet. He studied the failings and the promises of the World War and there he discovered von Boelcke and Richtofen. He learned that upon Richthofen’s death, a pedantic airman named Herman Goering undid his predecessor’s teamwork. Chennault was surprised to find that the ATS taught the newest and most theoretical precepts of massive bombardment but was teaching the fighter doctrine of 1918.

Never one to pale from expressing his opinions, Chennault quickly immersed himself in a two-front theoretical battle. First, he locked arms with his Air Corps brothers arguing for a decisive role for airpower in the heated debate between air and ground commanders. In this debate, his actions were short, but decisive in ruining a normal career. He first irritated Army Chief of Staff Gen Summerall and then Gen C. E. Kilbourne. His testimony to the Howell committee of the Federal Aviation Commission criticized restrictions placed upon the maneuvers of 1934 and the maneuver’s author, Gen Kilbourne. Weeks after the testimony Chennault’s name was removed from the Command and General Staff College list for the class of 1934-35. In the other theoretical battle, he disputed Douhet’s theories with the bomber advocates who dominated the Air Corps. The great questions were; what type of an air arm should a nation have; wholly offensive type (bombardment), balanced (airplanes of several types in ratio to each other), or mostly defensive (fighters)? What was the role of ground defenses? Can fighters intercept and defeat bombardment with any certainty? Chennault debated the merits of early warning, observation, bomber interception, and destruction in the ATS, through testimony, and in numerous articles published in the professional periodicals of the 1930s.

Nevertheless, the Douhet supporters won the debate of the decade. The pursuit tactics class was irrelevant for three years and fighters drifted into the doldrums. Championing a balanced approach to a theory of war, Chennault used the principles of former great battle captains to advocate roles for ground and air observation, pursuit, and bombardment. Chennault argued himself into exhaustion and into a corner, finding himself persona non grata in both the Army and its Air Arm. He was dejected that the only sympathetic ear for his theories were the Russians and the Nationalist Chinese. He had seen the writing on the wall regarding his career and was bitterly disappointed.

Nevertheless, the Douhet supporters won the debate of the decade. The pursuit tactics class was irrelevant for three years and fighters drifted into the doldrums. Championing a balanced approach to a theory of war, Chennault used the principles of former great battle captains to advocate roles for ground and air observation, pursuit, and bombardment. Chennault argued himself into exhaustion and into a corner, finding himself persona non grata in both the Army and its Air Arm. He was dejected that the only sympathetic ear for his theories were the Russians and the Nationalist Chinese. He had seen the writing on the wall regarding his career and was bitterly disappointed.

With his ideas rejected by the Army, Chennault accepted early medical retirement on April 30, 1937, and the next day he departed to complete a three-month survey of Chiang Kai-shek’s air force. Chennault foresaw the coming US conflict with the Japanese and thought that he could contribute to his country’s cause through the Chinese. He had paved his way into China by exchanging letters with Billy MacDonald, his old Flying Trapeze wingman. MacDonald and Williamson were working for a company that trained a small part of the China Air Force and Chennault would fight the Japanese from China for the next eight years, prove his theories, help the US adopt his doctrines, and support US strategy.

China is a nation of the lower strata of life with no vital spot whose capture would end the will or capacity to resist.

Tokyo newspaper complaint!

![]() Chiang’s intent and action were to maintain the delicate balancing act among China’s warlords, Chinese communists, Russians, Germans, Italians, and Americans to use the resulting confederation to expel the Japanese. In 1927, with China and Japan as enemies, Chiang identified the communists as a mortal threat. The fledgling Nationalist Chinese Army elicited assistance from the German advisers and sent the communists on their long march. The German and Italian advisers, and Russian advisers with hundreds of pilots and over 400 aircraft, allied with Nationalists to equip and train Chiang’s Air Arm. Nationalists, warlords, and communists agreed to disagree for the time being and to fight the common Japanese foe.

Chiang’s intent and action were to maintain the delicate balancing act among China’s warlords, Chinese communists, Russians, Germans, Italians, and Americans to use the resulting confederation to expel the Japanese. In 1927, with China and Japan as enemies, Chiang identified the communists as a mortal threat. The fledgling Nationalist Chinese Army elicited assistance from the German advisers and sent the communists on their long march. The German and Italian advisers, and Russian advisers with hundreds of pilots and over 400 aircraft, allied with Nationalists to equip and train Chiang’s Air Arm. Nationalists, warlords, and communists agreed to disagree for the time being and to fight the common Japanese foe.

The Japanese soon took exception to the German involvement in China and convinced the Germans to leave by July 1938. The Russians remained to fight the common Japanese enemy until Russia was imperiled by the Germans on their western front in 1942. The peak Russian advisory effort included over 1000 planes and over 2000 pilots, in rotation. The feuding Chinese factions were temporarily unified by Japan‘s 1931 occupation of Manchuria, the gnawing invasion of China‘s northern provinces, and the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge on July 7, 1937. Prior to the invasion triggered by the customs incident at the Marco Polo Bridge, Japan had increased her position on the Asian Mainland by every possible means short of war. By December 7, 1941, Japan controlled 95 percent of China‘s industry, one-fourth of her area, and ruled half her population.