Document Source: This archive – Georges S. Patton’s Desert Training Center – was written by Col John Kennedy, US Air Force (Ret) Col John Lynch, and Mr. Robert L. Wooley. The monograph appeared originally as issue number 47 in the Journal of the Council on America’s Military Past, in December 1982, Fort Myer, Virginia 22211. I have compiled it, added more information, and also several series of illustration photos to fit with the text. (Doc Snafu)

Document Source: This archive – Georges S. Patton’s Desert Training Center – was written by Col John Kennedy, US Air Force (Ret) Col John Lynch, and Mr. Robert L. Wooley. The monograph appeared originally as issue number 47 in the Journal of the Council on America’s Military Past, in December 1982, Fort Myer, Virginia 22211. I have compiled it, added more information, and also several series of illustration photos to fit with the text. (Doc Snafu)

Gen George C. Marshall in his Biennial Report of the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, July 1, 1941, to June 30, 1943, to the Secretary of War reported that the enlisted strength of the Army has been increased by 5.000.000 men and the officer corps has grown from 93.000 to 521.000. The gains included 182.000 officers and nearly 2 million enlisted men in the Army Air Force. Unprecedented growth included a 3500 percent increase in the Army Air Force proper, 4000 percent in the Corps of Engineers and 12000 percent in the service personnel of the USAAF.

In 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, after prolonged debate, were to receive Presidential approval for an armed force overall total of 11.264.000 to be reached by the end of 1944. Of this, the Army and Army Air Force were allotted 7.7 million. The number of divisions was set at 90. By 1945 the Army and Army Air Force were to total 8 million.

In 1942 the Army knew it must prepare for a variety of special operations under extreme conditions of climate, as exemplified in Norway, Libya and Malaysia, and operations by special means of assault such as amphibious and airborne. Gen Lesley J. McNair, later Commanding General of Army Ground Forces, wanted the Army to concentrate on the production of standard units and to give special training only to units that had completed their standard training, and only when operations requiring specialized training could be foreseen.

Theater training would be more realistic if and when specialized training was required. However, in the six months from March to September 1942, the Army Ground Forces activated four special installations: the Airborne Command (later Center), the Amphibious Training Command (later Center), the Mountain Training Center and the Desert Training Center.

The Desert Training Center was to remain active for 13 months and then was closed due to the inability of the Army Service Forces to properly support it during the War. Gen Marshall lamented the closing of the post-graduate course for his infantry and armored units but with most of the Army overseas and the few remaining divisions en route to ports of embarkation, the value of continued operation of the Desert Training Center (subsequently the California – Arizona Maneuver Area) was questionable.

Sixty-four infantry divisions were to be trained in the United States but only 13 were to train in the desert. Of the 26 divisions activated after July 1942, only one would come to the desert. A total of 20 of the 87 divisions of all types were to train in the Desert Training Center (DTC) in the California – Arizona Maneuver Area (CAMA) and these were the 5, 7, 8, 33, 77, 79, 89, 81, 85, 90, 93, 95 and 104th Infantry Divisions and Armored Divisions assigned were the 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 11. One of the Camp’s objectives is to memorialize military installations and units that no longer serve the role for which they were created. The World War II Desert Training Center (CAMA) and its abandoned military installations and units fit this objective precisely.

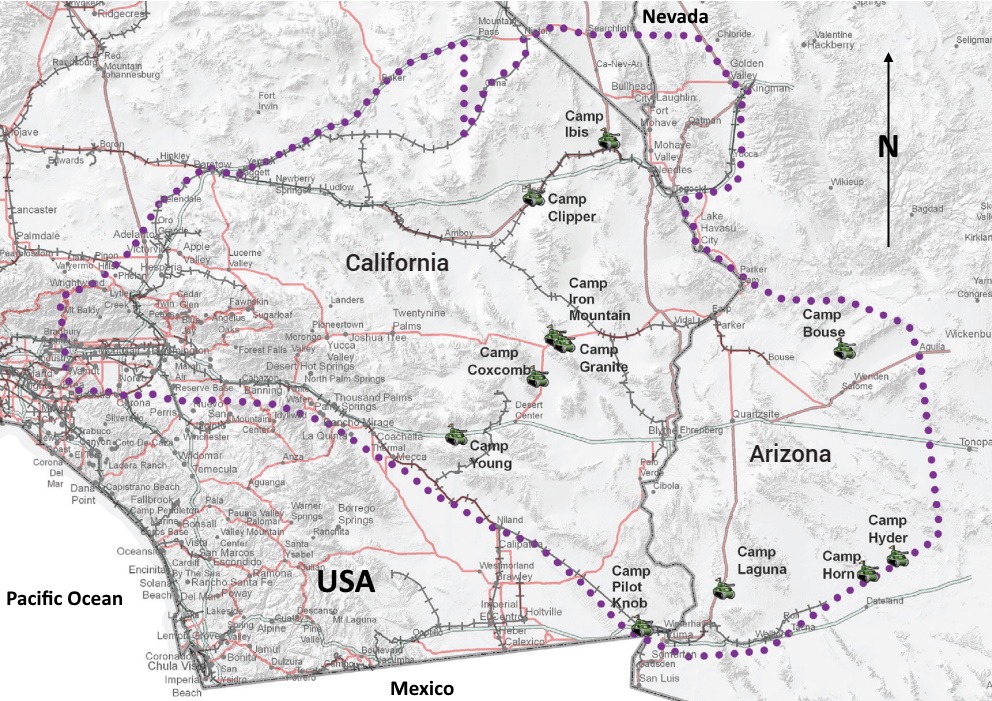

California-Arizona Maneuver Area, World War II

To set the stage, France was defeated, the attempt of the British to hold the Balkans and Greece had failed, and Gen Archibald Wavell was holding Egypt with a depleted force. On February 12, 1941, Gen Erwin Rommel arrived with his staff in Tripoli to join his Italian ally against whom he had formerly fought with distinction in World War One. Soon afterward, Gen George S. Patton received a new assignment. To a friend at the War Department, he wrote: I have been detailed to organize and command a Desert Training Area … I should deeply appreciate your sending it to me … any and all information, pamphlets, and what-not, you may have on the minutia of desert fighting, to the end that I may duplicate, so far as is practicable, the situation which exists in the desert of North Africa … Pardon me for writing you such a dry letter. We will try to correct the dryness when we see each other.

In January 1942, Patton announced, The war in Europe is over for us. England will probably fall this year. It is going to be a long war. Our first chance to get to the enemy will be in North Africa. We can not train troops to fight in the desert of North Africa by training in the swamps of Georgia. I sent a report to Washington requesting a desert training center in California. The California desert can kill quicker than the enemy. We will lose a lot of men from heat, but training will save hundreds of lives when we get into combat. I want every officer and section to start planning on moving all of our troops by rail to California. He added that In less than sixty days every I Armored Corps Unit was en route to Indio, California. Our final destination was a point in the middle of the desert near the town of Desert Center which in 1942 had a population of nineteen people. We were two commands, I Armored Corps and the Desert Training Center.

On March 4 1942, Patton flew to March Field, Riverside, California, then chose for his base camp a site 20 miles east of Indio. He selected locations near Desert Center, Iron Mountain and Needles for Division Cantonments where troops began to arrive on April 11, 1942. It is not clear just when the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff foresaw that our Army might have to fight in the deserts of North Africa. It may well be that Patton’s prodding was the decisive factor. The fact that the General became the first Commanding General of the Desert Training Command established the austerity, discipline, and high standards of unit and division training throughout the time at which the area was used. Patton’s tenure was rather short but his influence was established.

On March 4 1942, Patton flew to March Field, Riverside, California, then chose for his base camp a site 20 miles east of Indio. He selected locations near Desert Center, Iron Mountain and Needles for Division Cantonments where troops began to arrive on April 11, 1942. It is not clear just when the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff foresaw that our Army might have to fight in the deserts of North Africa. It may well be that Patton’s prodding was the decisive factor. The fact that the General became the first Commanding General of the Desert Training Command established the austerity, discipline, and high standards of unit and division training throughout the time at which the area was used. Patton’s tenure was rather short but his influence was established.

On February 5, 1942, McNair as Army Ground Forces Commander concurred in the recommended plan that a Desert Training Center be established. Patton was ordered to reconnoiter the area, which he did between March 4/7. The site was unlike any with which the Army was familiar, either in training or previous combat. The desert was hot, temperatures climbed to 120 degrees in the shade, vegetation was sparse, and rainfall averaged 3 inches a year. Perhaps as important as any terrain feature was the fact that it was a sparsely populated area and therefore would make it much easier to acquire for Army purposes. There were some units already in the area: a Field Artillery training area south of Indio, an Ordnance Section at Camp Seeley, an Engineer Board Desert Test Section at Yuma, Arizona, an Air Corps Depot at San Bernandino, Camp Haan at Riverdale, and an Army Air Base at Las Vegas, Nevada.

As the North African Campaign wound down in 1943, Rommel had given the Americans their first severe drubbing at the Kasserine Pass and Gafsa. Patton had long since departed from the Desert Maneuver Area, leaving in October 1942 for the North African Theater. The Morocco landing was successful but the near-collapse of the American front in Tunisia forced Gen Dwight Eisenhower to relieve Gen Lloyd R. Fredenall and replace him with Patton.

By March 1943 the North African campaign was in its final stages with FM Bernard Montgomery grinding in from the east and a revitalized and already veteran American force, now well beyond the nadir of Kasserine and Gafsa, coming from the west. So the primary mission of the Desert Maneuver Area to train the troops in desert survival and tactics did not apply to troops who were now coming to the maneuvers and who were to be deployed worldwide. Therefore the name of the Center was changed by War Department directive to the California Arizona Maneuver Area (CAMA).

The first directive by the War Department on November 25 1942 gave notice that the Army Ground Forces were in command, with a skeletal structure of the Center as the theater of operations. This later was amplified to restrict the use of the terms Theatre and Operations to employment within the DTC only. A second directive related to the Air Arm of the Center. Army Ground Forces’ control of ground and service units had been delineated in the original directive. The additional one stated that the Air Support Command – including combat and service units – and facilities for its use, which included Desert Center Airfield, Rice Army Airfield, and Shaver’s Summit Airfield were to be under the Commanding General of the Desert Center. (Can’t you just see the combined bristle of all air personnel at such a suggestion these days!) The third directive, dated January 14, 1943, enlarged the center to include the SOS installations existing or under construction, at or near Needles, Camp Young, Indio, Pamona, San Bernandino all in California and Yuma, Arizona. It declared that the primary purpose of assimilating the Center into a Theater of Operations was to afford maximum training of combat troops, service units, and staffs under conditions similar to those which might be encountered overseas.

As it turned out the designated combat zone was encircled by the designated zone of communications. This was something less than ideal for simulating true combat conditions. In the simulated desert area if you ran through the opposing forces you found you were back in your own zone of communications. By November 1943, the California-Arizona Maneuver Area had been enlarged and the IV Corps was in command.

As it turned out the designated combat zone was encircled by the designated zone of communications. This was something less than ideal for simulating true combat conditions. In the simulated desert area if you ran through the opposing forces you found you were back in your own zone of communications. By November 1943, the California-Arizona Maneuver Area had been enlarged and the IV Corps was in command.

This area, a barren stretch of wasteland, sand, rock, and cactus, was roughly oval-shaped and considering both the Communications Zone and the Combat Zone, was approximately 350 miles wide from Pomona, California, eastward almost to Phoenix, Arizona, and 250 miles deep from Yuma, Arizona, northward to Boulder City, Nevada. This area included at the time of the IV Corps Command, Camp Young, Camp Coxcomb, Camp Iron Mountain, Camp Granite, Camp Essex, Camp Ibis, Camp Hyder, Camp Horn, Camp Laguna, Camp Pilot Knob, and Camp Bouse. These were all temporary tent camps with a division being located at some of these, and at other armored cavalry, anti-aircraft, and field artillery units. The Corps Headquarters, California-Arizona Maneuver Area, was located at Camp Young along with station hospitals that served the outlying camps.

The Desert Training Center

The base camp received its name designation on May 12, 1942, deriving its name from Lt Gen Samuel Baldwin Marks Young, an Indian fighter who had operated in the region and was the first Army Chief of Staff. (During the Indian wars it was very common for camps or stations to be named after the officer who established them or the Commanding General of the district. Young had to wait a long time for his name to be thus enshrined; he had long since departed from the area and his terrestrial stay.)

The base camp received its name designation on May 12, 1942, deriving its name from Lt Gen Samuel Baldwin Marks Young, an Indian fighter who had operated in the region and was the first Army Chief of Staff. (During the Indian wars it was very common for camps or stations to be named after the officer who established them or the Commanding General of the district. Young had to wait a long time for his name to be thus enshrined; he had long since departed from the area and his terrestrial stay.)

On May 26 electric power lines from Parker Dam were in place. One of the original units to be transferred to the DTC was the 773rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (Col F.G. Spiess). It had previously taken part in the Louisiana and North Carolina maneuvers and was said to have traveled some 9.500 miles through seven states over a period of four months, but the men were to find a new experience at Camp Young where they arrived shortly after April 5, 1942.

On May 26 electric power lines from Parker Dam were in place. One of the original units to be transferred to the DTC was the 773rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (Col F.G. Spiess). It had previously taken part in the Louisiana and North Carolina maneuvers and was said to have traveled some 9.500 miles through seven states over a period of four months, but the men were to find a new experience at Camp Young where they arrived shortly after April 5, 1942.

Their official history relates that Camp Young was the world’s largest Army Post and the greatest training maneuver area in US military history. Eighteen thousand square miles of nothing, in a desert designed for Hell.

One soldier who had endured it reported that clothes, equipment such as water bags, radios, vehicles, armored vehicles of all types, and weapons were to be severely tested in this desert area.

Water in the Lister bags sometimes reached 90 degrees. After you have been inside the tanks for a while, water even at 90 degrees seemed cool. The tank destroyers were even hotter because they had open-top turrets. Sometimes the heat registered at 152 degrees. Inspection of tools and equipment was made early in the mornings or late in the evenings as any equipment or tools laid out on tarps by the individual vehicles, in the desert sun, could not be picked up as they would burn the hands.

Not all of the recollections of those who spent time in the hot sand of the Desert Traning Center were unpleasant. Another member of the 773rd Tank Destroyer Battalion recorded as follows my greatest experience for the desert was observing the beauties of nature, both in the desert and also the nearby mountains. Continuing, he said my worst experience was being stranded for two days in Pahlen Dry Lake in a disabled half-track with four crewmen during which time we had one can of sardines, one can of corn, and one and one-half canteens of water.

Before the first mass maneuver, and to add to initial confusion, an epidemic of yellow jaundice (hepatitis) swept the camps in July. This filled all of the hospitals in the California area. Convalescence of the patients was slow and this further delayed training. As we now know this was due to the contamination of the yellow fever vaccine given to the troops with a then undiscovered virus that caused hepatitis and jaundice. The yellow fever vaccine had been stabilized with human blood serum. The serum had been derived from volunteer medical students. This blood had been drawn from at least one student who had suffered from hepatitis previously. Thus, this widespread Army epidemic of hepatitis was iatrogenic in origin and it was devastating. Hundreds who received the yellow fever vaccine were thus inadvertently inoculated with another disease, hepatitis.

Before the first mass maneuver, and to add to initial confusion, an epidemic of yellow jaundice (hepatitis) swept the camps in July. This filled all of the hospitals in the California area. Convalescence of the patients was slow and this further delayed training. As we now know this was due to the contamination of the yellow fever vaccine given to the troops with a then undiscovered virus that caused hepatitis and jaundice. The yellow fever vaccine had been stabilized with human blood serum. The serum had been derived from volunteer medical students. This blood had been drawn from at least one student who had suffered from hepatitis previously. Thus, this widespread Army epidemic of hepatitis was iatrogenic in origin and it was devastating. Hundreds who received the yellow fever vaccine were thus inadvertently inoculated with another disease, hepatitis.

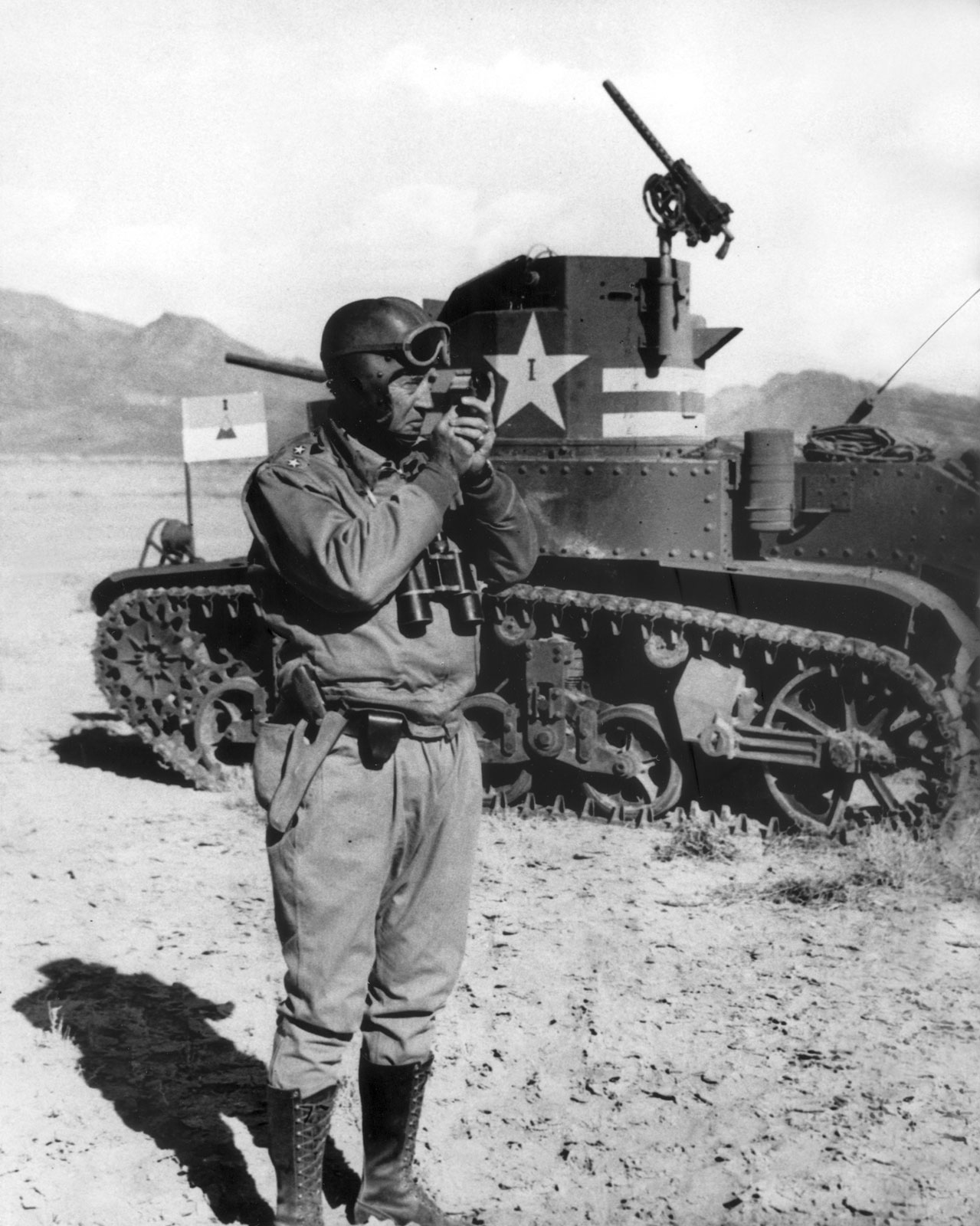

All accounts related that, as the first commanding general, Patton certainly stamped his brand on the training center. The hill from which he could observe a wide area was called The King’s Throne. It was a lone elevation between the Crocopia and the Chuckwalla Mountains and separated them both. The General used to sit or stand up there scrutinizing critically the line of march of tanks and motorized units below him. Detecting a mistake or way to improve, he would shout instructions into his radio.

All accounts related that, as the first commanding general, Patton certainly stamped his brand on the training center. The hill from which he could observe a wide area was called The King’s Throne. It was a lone elevation between the Crocopia and the Chuckwalla Mountains and separated them both. The General used to sit or stand up there scrutinizing critically the line of march of tanks and motorized units below him. Detecting a mistake or way to improve, he would shout instructions into his radio.

Something ought to be said about Patton’s radio. The official Army history of the Desert Training Center simply states the above but Porter B. Williamson in Patton’s Principles gives a detailed and delightful account of Patton’s communication system. This is how he describes the situation at the I Armored Corps Headquarters: our headquarters was approximately sixty miles east of Indio. Radio reception in our tents was poor due to the long distance between our portable radios and the broadcasting stations in Palm Springs and Los Angeles. Gen Patton’s first concern was always the welfare of the troops, so he purchased radio broadcasting equipment. The initial investment was his own money! Our Signal Corps troops installed the radio broadcasting equipment. The station broadcast only news and music. It was a quick method of communication with the troops. Gen Patton wanted to talk to the troops as often as possible. At a staff meeting he said, this new station could save several weeks of training. We can reach the troops, every one of them, as often as we need. In an emergency, we could reach every man in seconds. Williamson continued, our desert radio broadcasting station had one unusual feature. There was a microphone in Gen Patton’s office and the second microphone by his bed in his tent. Day and night Gen Patton would cut off all broadcasting and announce a special message or order from his personal mike. When the music would click off we knew we would hear this is Gen Patton. He would use it to commend the special efforts by the troops. He would announce, found a damn good soldier today! He would continue giving the name of the man and the organization. This officer encouraged every man and officer to give his best effort at all times. Often his harsh words for an officer would provoke laughter from others.